Spotlight: animal advocate and filmmaker Holly Cecil

Holly Cecil is a CETFA member currently doing research in the Human Dimensions of Climate Change program at the University of Victoria in BC. With a background of over twenty years of environmental and animal advocacy, her latest project aims to show Canadians the high costs of a meat-centered diet, not only to climate change but also to human health and animal welfare. Her 55-minute documentary Eating for a Healthy Planet: A Conversation with Canadians was launched on Earth Day 2013 and is currently receiving attention both here and abroad, due to the film’s content comparing European studies and initiatives as far more progressive than Canada’s. CETFA got a chance to chat with Holly about her documentary, as well as her journey to environmental and animal advocacy, and her upcoming projects.

Holly Cecil is a CETFA member currently doing research in the Human Dimensions of Climate Change program at the University of Victoria in BC. With a background of over twenty years of environmental and animal advocacy, her latest project aims to show Canadians the high costs of a meat-centered diet, not only to climate change but also to human health and animal welfare. Her 55-minute documentary Eating for a Healthy Planet: A Conversation with Canadians was launched on Earth Day 2013 and is currently receiving attention both here and abroad, due to the film’s content comparing European studies and initiatives as far more progressive than Canada’s. CETFA got a chance to chat with Holly about her documentary, as well as her journey to environmental and animal advocacy, and her upcoming projects.

CETFA: How did you become involved in animal advocacy?

Holly: I’ve always loved animals, and grew up on a family farm raising horses, dairy goats and sheep. As a child, I discovered first-hand how intelligent and social these animals were. I roamed our 160 acres with the goats while they browsed, and I spent endless hours observing their antics, their problem-solving abilities and complex social interaction. They taught me that we are so much more alike than we are different. From a young age, I’ve never understood the moral schism that humans create between animals and ourselves, to justify our exploitation of them. They are us – simply speaking – only, in hoofed and hairier bodies. The more we study them, the more we discover their surprising cognitive and emotional capabilities.

Holly: I’ve always loved animals, and grew up on a family farm raising horses, dairy goats and sheep. As a child, I discovered first-hand how intelligent and social these animals were. I roamed our 160 acres with the goats while they browsed, and I spent endless hours observing their antics, their problem-solving abilities and complex social interaction. They taught me that we are so much more alike than we are different. From a young age, I’ve never understood the moral schism that humans create between animals and ourselves, to justify our exploitation of them. They are us – simply speaking – only, in hoofed and hairier bodies. The more we study them, the more we discover their surprising cognitive and emotional capabilities.

In 1989 my future husband handed me Diet for a New America, which began a period of voracious reading to better understand how our diet and lifestyle impacts the suffering of animals. I immediately became a vegetarian (now vegan), and except for becoming a wife and parent, that still remains the best life decision I’ve ever made, with the most positive multiple outcomes.

I’ve divided the last twenty-five years between living in Canada and the UK, which has allowed me to better research European environmental and animal welfare initiatives. It troubles me that Canada is so much further behind other countries on many of these issues. For example, in 1999 the European Union instituted a ban on barren battery cages for laying hens to be fully enforced by 2012.[1] The same was true for the banning of sow stalls by 2013, initiated back in 2001.[2] In Canada, as you know, we’re looking at an industry delaying commitments to the phasing out of sow stalls until 2022. It’s shocking to me, and apparently to many European animal advocates too, that Canada has such a poor record on animal welfare.

CETFA: What inspired you to create this documentary?

Since 2008 I’ve focused a significant part of my research on the impact of diet on climate change. Through the documentary I wanted to show Canadians the many international studies reporting livestock agriculture as responsible for between 18 and 51 percent of all anthropocentric (human-induced) greenhouse gas emissions. The variation depends on the study and how the figures are assessed, but any way you slice it, it’s significant. It’s more than all forms of global transportation combined.

In 2009 the chair of the UN IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), Dr. Rajendra Pachauri, issued press releases encouraging the world to eat less meat as one of the most significant ways we can reduce our carbon footprint. The “Less Meat Less Heat” European Parliament summit in Brussels in 2009, addressed the huge range of environmental degradation caused by livestock agriculture – not only in climate change but also in water use, pollution of waterways, and other issues such as wasteful allocation of food crops fed to livestock and world hunger.

This is something you just don’t hear in Canada. Not only has our government pulled out of the Kyoto Protocol, but its public education on climate change makes not a single mention of these critical international studies on the impact of diet. Instead, Environment Canada focuses initiatives entirely in the energy and transportation sectors, for reasons which I uncover in the documentary. And in so doing, they’re missing a huge potential. I crunched the numbers, and we Canadians could fully meet our original emissions reductions commitment to Kyoto through the shift to a plant-based diet alone. It’s that influential. And with the win/win benefits to health care and animal welfare from a reduction in livestock agriculture, what’s not to like? It seems like a no-brainer to me, but I just didn’t see the information getting out there. So I decided to make the documentary.

I’m also an artist and recognize the power of visual media in social change. In research, we’re committed to poring over dense text in endless published studies. But that density of data has less appeal to the average person, already over-inundated daily with communication and print media. As humans, we evolved as visual creatures, and our learning is so much more empowered with visual stimulation. Although it’s unsettling to view visual footage of factory farms or slaughterhouses, for example, that experience drives these issues home in a way that a thousand fact sheets never could. I’m a novice film-maker, but recognize that this medium is the single most effective tool for social change and reaching all ages in our culture.

CETFA: What did you discover during the making of the documentary?

What I expected – yet still was surprised by – is how much work goes into the making of a film! I now better appreciate the contributions of the endless list of names we see scrolling across the screen at the end of any presentation. Likewise, Eating for a Healthy Planet could never have happened without the contribution of several participants who provided visual footage, including CETFA, Yann Arthus-Bertrand and the European Fondation Goodplanet [sic], musicians like Moby, and others. What’s heartening is that so many of us around the globe are working to achieve similar goals, so to find ways to share our resources only further strengthens each other’s work. And you end up meeting some pretty fantastic people along the way, too.

What I expected – yet still was surprised by – is how much work goes into the making of a film! I now better appreciate the contributions of the endless list of names we see scrolling across the screen at the end of any presentation. Likewise, Eating for a Healthy Planet could never have happened without the contribution of several participants who provided visual footage, including CETFA, Yann Arthus-Bertrand and the European Fondation Goodplanet [sic], musicians like Moby, and others. What’s heartening is that so many of us around the globe are working to achieve similar goals, so to find ways to share our resources only further strengthens each other’s work. And you end up meeting some pretty fantastic people along the way, too.

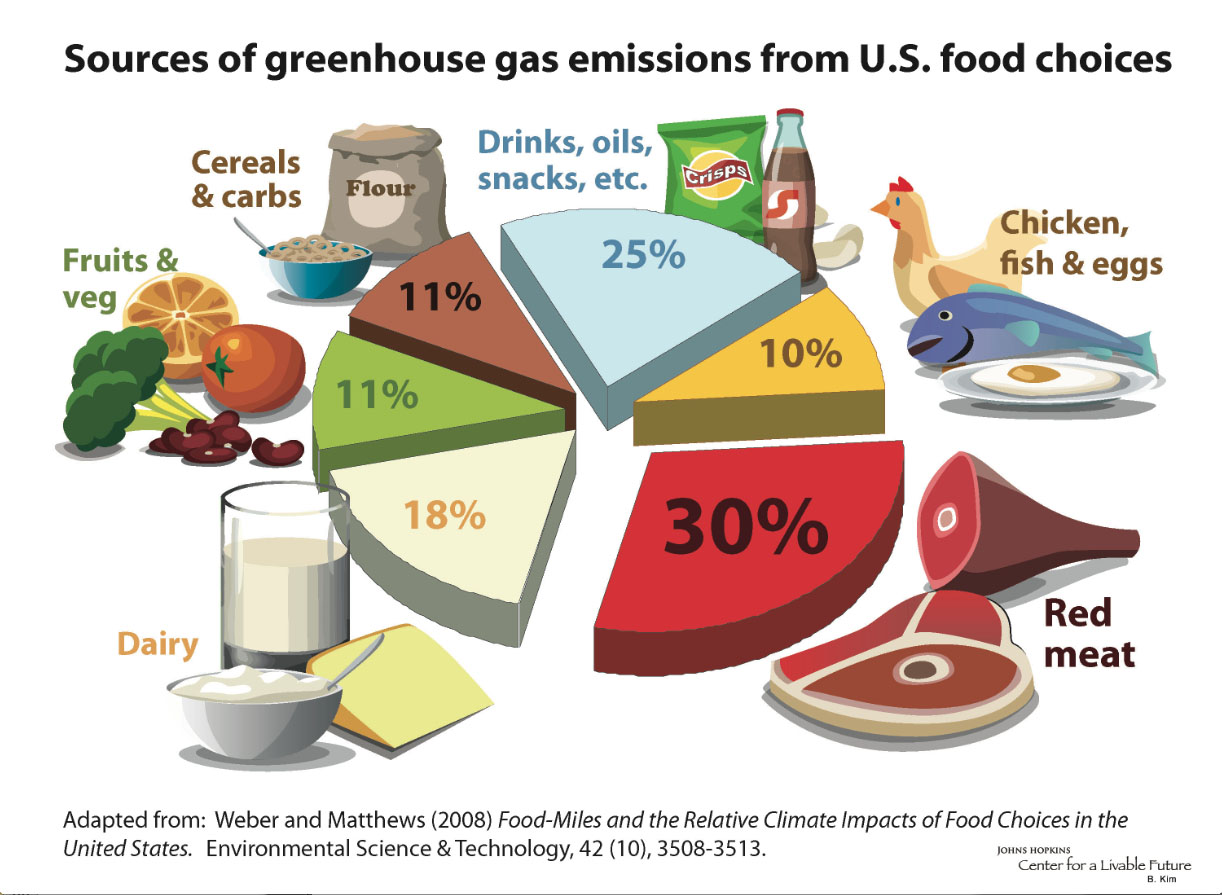

In terms of research, what was quite surprising was discovering that food miles are not the best indicator of the actual greenhouse gas emissions inherent in food, nor are all foods equal in that respect. Despite most foods being transported over long distances, it’s the production phase and not transportation which dominates their impact. Transportation from producer to retailer comprises only four percent of a food’s emissions, on average. The start-to-end process of raising, slaughtering and distributing meat, fish,eggs and dairy comprise almost 60 percent of greenhouse gas emissions inherent in household food.[3] This explains why the chair of the UN IPCC would go public to encourage a reduction of meat as one of the most effective ways individuals can reduce their carbon footprint.

Although food miles initiatives such as the 100 Mile Diet have become popular ways to promote local agriculture, people are lulled into a false sense of accomplishment in thinking local meat equals fewer emissions. It doesn’t. Studies report that shifting just one day per week’s worth of calories from red meat and dairy products to a plant-based diet achieves more GHG reduction than eating all locally sourced food, seven days per week.[4] That’s very significant, and explains the importance of achievable initiatives like Meatless Mondays which the documentary promotes.

CETFA: What did you find the most troubling?

I think what impacted me most in researching for the film is the extent of animal suffering around the world. With huge developing nations like China becoming major players in industrial livestock agriculture, the numbers of animals suffering globally are staggering.

We know from the UN FAO (Food & Agriculture Organization) that approximately 56 billion animals worldwide are slaughtered each year for food.[5] That’s eight times the human population. Every year. The numbers are mind-numbing. Studies in animal cognition tell us these animals are not the automata that the industry would prefer to think of them as. They have evolved sensory organs that often surpass our human ones. Given proper conditions, they have the potential for learning, affection, and rich social lives, not unlike young children. Try to imagine children being put into the conditions most animals are subjected to in factory farming, and you can’t; it’s horrific, surreal. Yet what is the difference?

Timothy Pachirat, author of Every Twelve Seconds: Industrialized Slaughter and the Politics of Sight, spoke about his experience as a Yale graduate student working undercover in an American meat-packing plant. Even while being herded along chutes toward the kill floor, individual cattle would still pause and extend their noses to sniff his outstretched hand. He describes that even in their last moments, they still accepted his reaching out to them to make human-animal contact.[6] Even after a lifetime of abuse, animals continue to trust in the remote potential for human compassion. And what do we do with that trust?

CETFA: So this is not just about the environment, but also animal cognition and psychology?

Absolutely. It’s all connected. I’d like to better understand how compassion becomes shut down in the human psyche. This begins to address some pretty deep dysfunction in our culture. The violence we see around the world which impacts women and children, religious, ethnic or sexual minorities, has the very same roots in our violence toward animals. And although family farms are a vast improvement on factory farming, they don’t seem to see the irony in using oxymoron marketing terms like raising ‘humane meat’ for niche markets. Humane meat. Ethically slaughtered. Since the horrors of Auschwitz, as one example of the world coming face to face with the industrial killing of sentient life, how can we call any form of slaughter ethical?

Throughout history and particularly advanced during the Enlightenment, philosophers recognized that human violence towards animals was consistent with the capacity for violence against other humans. Studies in psychology report that the cycle of violence begins in youth. Children who are abusive to a pet are quite often acting out violence experienced or witnessed in the home. Research in psychology and criminology finds that more than half of serial murderers admitted to hurting or torturing animals as children or adolescents.[7]

Where do our attitudes toward animals begin? Children start out in life being instinctively attracted to, and compassionate towards, animals. Jim Mason’s excellent book An Unnatural Order describes how animals literally ‘animate’ our earliest imagery and relationship to nature. Yet our innate desire to extend compassion to animals becomes overridden by cultural indoctrination. Children’s plasticity to parental and peer instruction, an evolutionary trait which permits our complex brain development, in this case backfires as we accept inherently dysfunctional behaviours that can lead to violence. We learn from our parents that it’s ‘normal’ to kill and eat animals, even though as humans we have no nutritional dependency on animals that a plant-based diet cannot easily fulfil. Exploitation of animals is so central and ingrained in our culture, that to even begin to question it is perceived by most people in only two ways: either with incomprehension, or as a threat to their way of life.

CETFA: Can you give a specific example of indoctrination?

One interesting example is the 4H youth program in our Canadian agricultural communities. Under the guise of instilling positive animal husbandry values, children are encouraged in the spring to choose a newborn calf, lamb or goat kid, for example, to raise as their own as part of their local 4H club. They spend the summer raising, grooming, and training it to lead and eventually compete in the show ring during the autumnal fairs held across our country. And in this process they form very strong emotional bonds with this animal. They often learn how smart, how social, how funny, how affectionate animals can be. Then after the fairs are over they have to send that animal to auction, to slaughter. And these kids are devastated. It’s like sending a friend to the gallows. But it’s considered part of the ‘educational experience’ for these children to learn the annual economic cycle of livestock agriculture. Any innate respect or compassion for the animal that grew through their months of interaction with it is devalued as emotional or impractical. I speak from experience. The adults involved are no doubt well-meaning and believe they’re instilling positive values, but viewed objectively they are simply repeating the indoctrination they themselves received. And that’s how we perpetuate the cycle of devaluation and exploitation of other species. If our parents did it, it must be right. But it’s not.

Ghandi is attributed as saying, “The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated.” I feel our relationship with non-human animals reflect deep dysfunctional problems in our culture that are connected to so many of the other problems we despair over, such as violence, human trafficking, child abuse. None can be solved without addressing these deeper issues and common roots.

CETFA: Are there actions that people can take?

Yes! The problems that our culture now faces – environmental, health, and social issues for example – have become so significant that a growing number of people are beginning to connect the dots and stand up for change. For example, the urgency of climate change is waking people up to the many environmental costs of industrial livestock agriculture. Exposure to imagery of factory farming then leads to interest in animal welfare and reducing suffering. Then they learn about the health benefits of reducing meat consumption. It’s a win-win-win scenario that is empowering a lot of positive change.

It’s shocking that in Canada, around one in every four people is now clinically obese, and almost two-thirds of our population is classed as overweight.[8] Our addiction to meat is literally killing us. It drives our top killers such as heart disease, strokes and diabetes. The strength of a plant-based diet to lower body mass index, type II diabetes, heart disease and several types of cancers, and extend life expectancy in long-term vegetarians by up to ten years is well documented in long term studies and peer-reviewed medical journals.[9] International initiatives such as Meatless Monday (now active in 24 countries) and Chomp Climate Change are helping spearhead these transitions to a more plant-based diet.

It’s no longer fringe. Last year in the US, 18 percent of people ate vegetarian at more than half of their weekly meals.[10] It’s amazing. In the Netherlands, 40 percent of citizens now make three or more days per week entirely meat-free, in an effort to reduce climate change.[11] In Canada, it’s an indictment on our government that any changes here are happening more from citizens taking action, through public awareness and social change, than from education from Environment Canada or Health Canada. The Dietitians of Canada at least are making some effort. A better resource for anyone wanting more info on diet and health studies is PCRM (Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine).

CETFA: What misconceptions do you think people still have?

On a web site reporting on the tens of billions of livestock contributing annually to climate change, I read a reader’s comment that would have been funny if it didn’t reveal such a tragic misunderstanding: “Well, if all these animals are causing climate change, isn’t it good we keep eating more of them to lower their populations?” It shows how out of touch the average person has become from their food supply, from the industrialized agriculture that perpetuates these massive numbers through rigorous breeding programs. Positive dietary transitions can reduce the demand for these numbers and the resulting suffering worldwide. And as the numbers of livestock bred and raised for food worldwide is reduced, consumers can demand that those remaining animals are maintained in cruelty-free environments.

Another funny quote I sometimes hear from baby boomers is, “Well I tried being vegetarian back in the seventies, and it didn’t work for me.” Today that’s like saying, “Well I tried recycling, but it didn’t work for me.” It’s not an option anymore. Scientists are warning that by 2050, a global population of nine billion will force us to limit our consumption of animal-based foods to 5 percent of total calories to avoid food and water shortages in a climate-stressed world.[12] Whether you start at one day a week, or go fully vegetarian or vegan, it’s one of the most significant ways you can better the environment and the health of animals and yourself.

Many meat-eaters are worried about feeling deprived if they go meat-free one or more days a week, but the variety of plant-based foods now is amazing. Honestly, since going meat-free I now enjoy sitting down to a meal so much more. I’ve learned how to cook Indian, Thai, Japanese, Jamaican … the rich cuisines of these cultures already emphasizes plant foods and with diverse flavours that far surpass the old ‘meat and two veg’ that I grew up with. The recent film Forks Over Knives has done a fantastic job showing the health benefits of eating green and they have some amazing recipes on their web site. Check it out.

CETFA: What’s next for you?

As I’ve said, I’m also really interested in how the roots of animal exploitation go deep in our culture and in our species history. I recently saw an excellent lecture by Melanie Joy, a professor of psychology and sociology from U of Massachusetts and author of the book Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs and Wear Cows. She heads the Carnism Awareness & Action Network. The term ‘carnism’ addresses these deep-seated assumptions in our culture that exploitation of animals is a given and not a choice.

She also raises the important issue of what is termed ‘secondary trauma’ – to those witnessing violence, either to human or non-human animals. This might interest some of your readers, particularly those who are active animal advocates and may have witnessed animal cruelty either in person or on film. To anyone with an ounce of empathy, witnessing the pain and suffering of an animal can be excruciating, especially when you are powerless to stop it. This secondary trauma can either go unrecognized or devalued – for we view it as insignificant compared to the trauma of the animal we are working to help – and therefore can undermine our long-term health and endurance to continue that work. Dr. Joy recommended a book called Trauma Stewardship which I found very helpful, particularly just to identify that secondary trauma even exists and should be taken seriously. Particularly for those with long-term exposure to animal suffering in advocacy work, you have to find ways to process those experiences and find the strength to keep going, to continue working over the long haul.

Having focused on climate change, I now want to make a film more directly addressing animal welfare and how our culture turns a blind eye to the suffering of animals, particularly livestock. I really admire the work that CETFA does, and Twyla Francois’s advocacy (who was head of investigations until her move to MFA Canada in 2012) featured in the documentary No Country for Animals. It’s equally critical to document the conditions and treatment of livestock, as it is to challenge the deeper psychological and cultural roadblocks that prevent the general public from even wanting to think about these issues, let alone watch them on screen. Why do the majority of people turn a blind eye, while a few care so passionately? Animal advocates have been marginalized for decades – centuries, really – as either extremist or over-emotional. Research in animal cognition and behaviour is now helping back up long-standing animal advocacy, and drive important legislation, such as the protection of the great apes. However these laws are more progressive in other countries than they are in Canada, particularly in respect to our pitiful laws regarding livestock agriculture and transport. So we have our work cut out for us.

For more information:

Eating for a Healthy Planet: A Conversation with Canadians (55 minute documentary) [or 4.5 minute trailer]

Meatless Monday Canada; Meatless Monday US; Meatfree Mondays UK

References:

[1] “In 1999 the EU agreed a Directive on Laying Hens (1999/74/EC) that resulted in the banning of the most inhumane of these systems, the barren battery cage. The EU allowed producers a 12 year phase-out period, bringing the ban into effect on 1 January 2012.” See Compassion in World Farming web site: <http://www.ciwf.org.uk/what_we_do/egg_laying_hens>

[2] “In 2001 the EU agreed the Pigs Directive (2008/120/EC), laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs, one of the results of which was the banning of the sow stall from 1 January 2013. The EU allowed producers a 11 year phase-out period and exemptions for the first four weeks of a sow’s pregnancy as well as the week before farrowing. The ban on the sow stall has major welfare implications for breeding sows. Instead of spending 16 ½ weeks of her pregnancy in a stall, a sow will be kept in a group housing system for the majority of the time, allowing her to move around and interact socially with other sows.” See Compassion in World Farming web site: <http://www.ciwf.org.uk/what_we_do/pigs/the_2013_sow_stall_ban.aspx>

[3] Christopher L. Weber and H. Scott Matthews, “Food-Miles and the Relative Climate Impacts of Food Choices in the United States,” Environmental Science & Technology, 2008:42, (3508–3513), 3513.

[4] Ibid., 3512-3513.

[5] FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) FAOSTAT. 2008. Accessed 20 Dec., 2012. <http://faostat.fao.org/>

[6] James McWilliams, “Interview with Timothy Pachirat,” June 7th, 2012. <http://james-mcwilliams.com/?p=1577>

[7] Jeremy Wright and Christopher Hensley, “From Animal Cruelty to Serial Murder: Applying the Graduation Hypothesis,” International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 47:71, 2003, (71-88), 73.

[8] Margot Shields and Michael Tjepkema, “Regional Differences in Obesity,” Health Reports, Statistics Canada, Catalogue 82-003, 17:3, Aug. 2006, 1.

[9] Gary E. Fraser, MB, ChB, PhD; David J. Shavlik, MSPH, “Ten Years of Life: Is It a Matter of Choice?” Archives of Internal Medicine, Vol. 161, 2001, (1645-52), 1645.

[10] Those who reported eating vegetarian at more than half their weekly meals, but not all the time: 14%; those who reported eating vegetarian always: 4% (vegetarian and vegans); total 18%. 2012 National Harris Poll. <http://www.vrg.org/blog/2012/05/18/>

[11] De Bakker E and Dagevos H (2012). “Reducing Meat Consumption in Today’s Consumer Society: Questioning the Citizen-Consumer Gap.” J Agric Environ Ethics 25:877–894

[12] John Vidal, Environment Editor, “Food Shortages Could Force World into Vegetarianism, Warn Scientists,” The Guardian, Aug. 26, 2012. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/global-development/2012/aug/26/food-shortages-world-vegetarianism> Accessed Sept. 15, 2012.